Over the past year or so I have developed a new way of explaining functional disorders to patients. It has generally been well-received, so I thought I would share it here in hopes that it will be useful and helpful to someone. This post is aimed at people with functional disorders and the doctors who take care of them.

Functional disorders produce distressing, disabling, and involuntary symptoms that are primarily caused by psychological factors rather than by physical diseases. Many patients have a hard time grasping this concept, and many more jump to a simplistic conclusion that the diagnosing doctor is just saying it is “all in their head.” This serious condition deserves a serious explanation, and a serious amount of time to communicate it.

Let’s dig in.

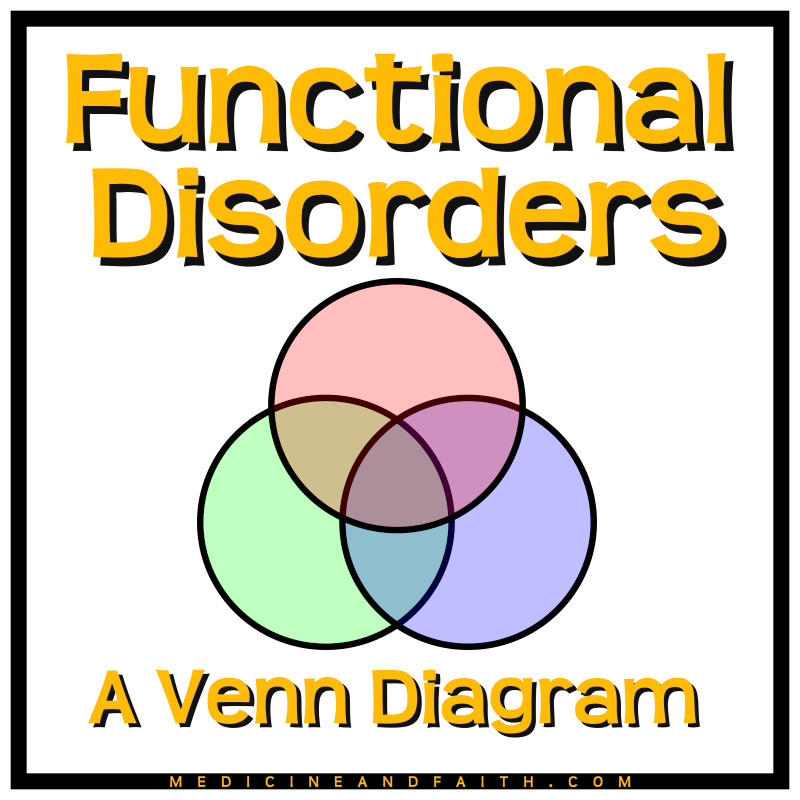

You can think of functional disorders as living in the overlap zone between three big psychological concepts. All three of them are things that normal people do, but some people do them more than others and combine them in interesting ways.

1. Somatization

The first concept is somatization, which means experiencing your emotional state with physical symptoms. Again, all of us do this to some degree or other, but some people are extremists. In a previous post on this subject I described the common physical symptoms that people experience during public speaking: dry mouth, butterflies in your stomach, stuttering, cold sweats, tremors, increased heart rate, etc. Another familiar example is a panic attack, which causes shortness of breath, chest pain or pressure, and a feeling of suffocation.

The important thing to understand is that these symptoms are involuntary, caused by your emotional state, and not caused by a disease in your body. Also, it is a normal human experience.

I somatize from time to time, like everyone else does. When I was under a lot of stress during residency I had some weird body symptoms, and they totally resolved when my work-life balance and sleep deprivation improved. A few months ago I had a tremor during a stressful experience.

2. Alexithymia

Alexithymia refers to those times when you have a hard time reading or expressing your own emotional state. We all have times when we are not very tuned in to how we are feeling.

For example, imagine you are in the kitchen by yourself getting some food, and a family member or roommate walks in and starts talking to you. Suddenly you snap, and say something rude or angry. The look of surprise on their face is your first clue that you have done something wrong.

How did this happen? You quickly apologize, and then examine yourself. Why did you say or do this offensive thing, seemingly unprovoked? Then you realize that you are in a bad mood. Something in your life is weighing you down, but you weren’t really conscious of it until you reacted so negatively.

Alexithymia is a normal thing that we all experience, and some of us experience it more often.

Already we can see that interesting things can happen when you overlap alexithymia with somatization. Imagine that you are having physical symptoms caused by your emotional state, but you are not really aware of what your emotional state is. You could be experiencing symptoms that you don’t know the cause of, and you could misattribute them to a physical disease.

3. Dissociation

The third concept is usually the most familiar to my patients. Dissociation means disconnecting from or losing awareness of consciousness, memory, or your own body. It is not an intentional or voluntary experience, like a switch you can turn off and on; it happens automatically. We all do something like this from time to time, like when we space out in math class or get in the zone while working.

The really interesting thing about dissociation is that it is commonly used as a coping strategy or defense mechanism by people who have been severely abused in early childhood. This makes sense. If you are powerless to stop an abusive relationship, then having a method to mentally check out for a while could protect you from fully experiencing some of that abuse.

But excessive amounts of dissociation can cause problems in your everyday life, obviously.

The Overlap Zone

Imagine that you are on the triple overlap zone of the Venn diagram above, experiencing physical symptoms from your emotional state, but being confused about the source of the symptoms because you can’t read your emotional state, and having some degree of dissociation so that your awareness or your consciousness is impaired. That is a recipe for a non-epileptic seizure episode.

If the dissociation causes an internal disconnection, where you lose contact with a part of your own body instead of with the outside world, then you could experience paralysis or loss of sensation in that part of your body.

At this stage of the discussion I usually pause to ask if all of this makes sense to the patient. This helps me gauge their comprehension, and it gives me some valuable feedback about how much they believe it. A positive response to this lecture is not necessarily diagnostic, but I think it is very supportive. It is also a good prognostic sign.

A lot of the time patients act like they are seeing themselves in a mirror for the first time.

Next Steps

An effective diagnostic interview is the first step in treating a functional disorder, because patients who can understand and accept the diagnosis are far more likely to improve. That is why it is worth my time to have this conversation with patients, even if it means falling behind on my schedule that day. Sometimes — rarely, in my experience — patients will be cured just from knowing the diagnosis.

The next step for most patients is some kind of counseling. Functional disorders are like coping strategies, so patients benefit from learning more effective methods of coping (cognitive behavioral therapy, supportive psychotherapy, etc.), and from addressing root causes (trauma counseling, dialectical behavior therapy, etc.). A good diagnostic interview can motivate patients to get the help they need to address the underlying psychiatric conditions.

Final Thoughts

I have seen a massive change in my specialty’s approach to functional disorders during my career. When I was in residency it was a game of “diagnose and adios,” where the emphasis was on being a keen diagnostician and then washing your hands of the patient as soon as possible. Over the last 10 years we have stopped treating the patient like a hot potato and have scheduled more follow up appointments to help them understand and accept the diagnosis, and to make sure they are connected with appropriate mental health services.

Neurologists taking a more longitudinal role in the care of functional disorders is good for both patients and doctors, I think. It helps patients feel that their condition is important and that their doctor is helping them. It also helps the neurologist to be more patient and empathetic. Having a bigger investment in the patient makes you less dismissive during the diagnostic interview, where therapeutic rapport is critical.

And it is a big investment! It takes mental and emotional energy to have this conversation effectively, and it can be taxing to have it very often. But it makes such a difference to the patient!

I hope that this post will be helpful to other doctors and providers who diagnose patients with functional disorders. In my own clinic I draw the diagram by hand each time because I think it anchors the patient better to see the concepts one at a time. When I am done I hand the drawing to the patient and tell them to hang it on their fridge. You can download a pdf handout or a presentation slide to use or adapt for your own practice if you wish.

I would love to hear any success stories with this diagnostic interview, or any revisions that you find to be helpful. Please comment below or send me a private message using the contact form on this page.

Alan B. Sanderson, MD is a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and is a practicing neurologist.

Interesting. How would this relate to PTSD?

LikeLike

There’s a big overlap. Some people with PTSD develop functional disorders.

LikeLike

Interesting work you do. Thanks for sharing.

LikeLike